How would you feel if you were harmed by a medicine you took as prescribed and then learned that the drug company wasn’t liable — even though it knew about the risk and didn’t tell you or your...

Suzanne Robotti

Bladder control tips for men

It’s a fact that as men age, the prostate enlarges, and that causes frequent, sometimes painful urination. But you don’t have to reach for a pill or submit to surgery. Small behavior changes can...

Bug repellents: Which ones are safe?

It’s summer, the time of year when we seem to be most surrounded by bugs. Most of us use bug repellents to keep bugs away. But, which ones are safe? DEET: Many bug repellents use DEET, which is...

“Right to try” experimental drugs is bad deal for...

It sounds like a good idea. Patients who are terminally ill would be allowed to ask pharmaceutical companies to try drugs that are not yet approved. If a patient who is dying has tried other...

Seven questions for women to ask about meds

Each year, an estimated 4 million Americans rush to the doctor or the ER in response to an adverse reaction to a prescription drug. So while medications can save or improve your life, they also...

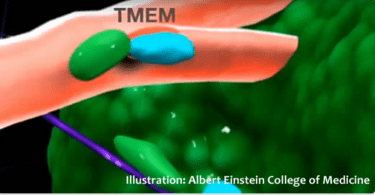

Spying on cancer

What if a new technology could detect aggressive cancer cells, effectively spying on cancer? Researchers think it could improve the chances of treating these cancers. Some cancers are aggressive and...