Representative Mark Pocan (D-WI) introduced eight bills aimed at strengthening traditional Medicare and reining in some of the worst practices in the privately-run Medicare Advantage business. For...

Wendell Potter

Will insurers dump Medicare enrollees with high health costs to...

Wall Street is speaking loudly to Medicare Advantage insurers: If you want us to stick with you, keep dumping seniors who are pinching your profit margins. Investors continue to punish UnitedHealth...

DOJ takes on health insurers for price-fixing

In a significant move, the DOJ filed a “statement of interest” in federal court this week, siding with hundreds of physicians who accuse top insurers and a firm formerly known as MultiPlan —...

UnitedHealth overbills the VA by hundreds of millions of dollars

At a recent Congressional hearing in Washington, Rep. Mark Takano (D-California), the top Democrat on the House Veterans Affairs Committee, directed a series of questions to the CEO of the health...

UnitedHealth, CVS and Cigna helped fuel opioid crisis

[Editor’s note: I am reposting this piece because it brilliantly exposes how the drug middlemen “PBMs,” who are supposed to be delivering value to Americans, deliver value primarily...

Project 2025: A plan to destroy Medicare quickly

Project 2025 proposes to make private Medicare plans, also known as Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, the default enrollment option for beneficiaries. Similar to Trump-era programs that automatically...

US health care system ranks dead last among 10 of the...

The Commonwealth Fund this week released its biennial ranking of the health systems of 10 of the world’s richest countries, and once again the United States comes in dead last – as it has for the...

Medicare Advantage: The numbers speak volumes

The Center for Health and Democracy put together these facts illustrating the high cost we pay for Medicare Advantage, both financially and physically. In Medicare Advantage, our taxpayer dollars are...

How big insurers please Wall Street’s investors

The big for-profit insurers made more than $40 billion in profits during the first six months of this year but Wall Street doesn’t consider that nearly enough. Investors have been shifting money...

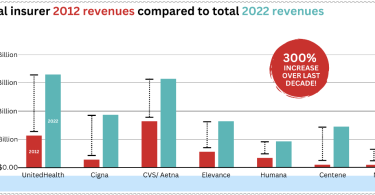

Big insurer earnings total $1.25 trillion in 2022

Big Insurance revenues and profits have increased by 300% and 287% respectively since 2012 due to explosive growth in the companies’ pharmacy benefit management (PBM) businesses and the Medicare...