In an op-ed for the New York Times, former Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid...

Medicaid

Coronavirus: Lawmakers ignore horrific number of nursing home...

David Dayen writes for The American Prospect on the horrific number of deaths at nursing homes...

Coronavirus: Watch out for Medicare fraud

Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar reports for AP that fraudsters are trying to sell older adults and people...

Here are ways Congress can ensure the well-being of older adults...

Congress has just passed an $8 billion emergency spending package to help address the coronavirus...

Trump administration acts to address some needs of older adults...

With the coronavirus spreading quickly in the US and few federal efforts to date to contain it, the...

Trump confirms his plan to cut Medicare, Social Security

If you value your Medicare and Social Security benefits as much as the vast majority of Americans...

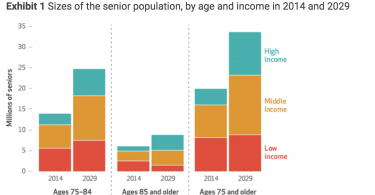

Many middle-income older adults will be unable to pay for...

A new paper in Health Affairs projects that many middle-income older adults will not be able to...

Medicare and Medicaid: How they work together

Nearly 12 million people with Medicare also are enrolled in Medicaid. If you have Medicare and...

Organizing older adults to defend our health care

A recent paper by Community Catalyst’s Leena Sharma, Carol Regan and Katherine Villers...

HHS head says we need Medicare for big system change

What does it take to drive big health care system change? Trump’s HHS head, Alex Azar, recognizes...