GLP-1 drugs, like Wegovy, Ozempic and Zepbound, are helping millions of Americans lose weight. At...

Health insurance

Public health insurance lowers health care costs and covers the...

Medicare for those who choose it–public health insurance–would lower people’s health...

Insurers misuse prior authorization even for simple treatments

One big insurer, Anthem, denied coverage inappropriately to a woman who needed medicine to ward off...

Insurer provider directories misleadingly include physicians who...

Max Blau reports for Pro Publica on how the big insurers provide their enrollees with misleading...

Why health insurers deny necessary care and get away with it

If you’re wondering why insurance companies deny necessary care and get away with it...

As the US population ages, how will people afford long-term care?

Americans are finding it increasingly difficult to meet their and their loved ones’ long-term...

Can we fix our broken health care system without reining in...

Aaron Carroll writes for the New York Times about how to fix our broken health care...

Don’t rely on Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs for the...

I promoted Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs a while back as a way to get low-cost generics. As it...

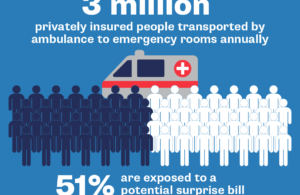

When will Congress address surprise ambulance bills?

Surprise medical bills are all too common, leaving millions of Americans with health care costs...

HCA hospital system is charged with overtreating patients to...

Last week, I wrote about a hospital that incorrectly charged a patient for a costly service it did...