Caring for an older person with multiple needs can take a toll physically, emotionally and...

Long-term care

Planning for long-term care; you’re more than likely to...

Howard Gleckman reports for Forbes on why everyone 65 and older should expect to need long-term...

PACE helps older adults stay in their community

The Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is a home and community-based program...

Caregiving has become increasingly common, challenging and costly

We are an aging population. And, caring for older adults is costly. Not surprisingly, family...

Government-administered long-term care insurance is long overdue

Since the start of the novel coronavirus pandemic, more than 46,000 people have died in nursing...

Coronavirus: What happened at a nursing home in Washington

Katie Engelhart reports for California Sunday on what happened at Life Care Center of Kirkland, the...

Coronavirus is making it harder to get long-term care

The financial and emotional toll of caring for older adults has always been enormous. The novel...

Will nursing homes and assisted living facilities be able to...

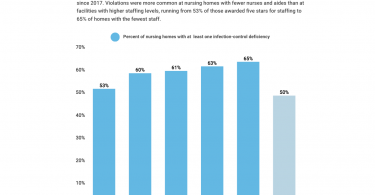

Jordan Rau reports for Kaiser Health News that for quite some time nursing homes have not been...

Free local resources to help older adults

If you’re looking for free local resources to help older adults, your local Area Agency on Aging...

Evidence suggests privatized Medicaid long-term care may put...

The US health insurance system has become increasingly privatized. One big trend is in the Medicaid...