Social Security just announced the cost-of-living adjustment, COLA, for Social Security, and the...

Social Security

Five ways Congress could weaken Social Security

Of all the federal government programs in the U.S., Social Security is perhaps the most...

New cuts proposed for Social Security Administration

Back in June, I reported for Just Care that Congress was keeping the Social Security Administration...

Strengthening Social Security Act of 2016

On September 9, U.S. Representatives Linda Sanchez and Mike Honda of California introduced...

Social Security’s 81-year impact

Daniel Marans writes for the Huffington Post about Social Security’s 81-year impact. From its...

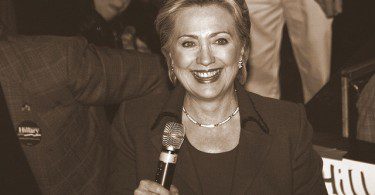

Clinton, Democrats on Medicare, Social Security

In sharp contrast to the 2016 Republican Party platform, the Democratic Party platform proposes to...

Trump, Republican platform on Social Security, Medicare and...

Trump has not spent much time talking about his vision for Social Security, Medicare and health...

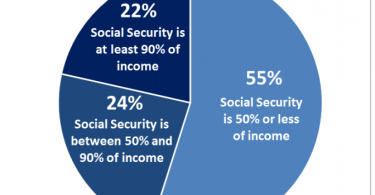

Social Security benefits us all

Social Security is our nation’s premiere social insurance program promoting security for roughly...

Congress keeps Social Security from spending its own money to...

It’s bad enough that Congressional leaders want to cut Social Security benefits. But did you...

Expand Social Security, don’t means test it

Ever since a few weeks ago, when President Obama joined with Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton...